Crypto Aggregation Theory (ft. Bridges)

Pt1. The Evolution of Aggregation Theory

Introduction

The case for aggregation in crypto (and specifically in the bridge industry) is layered and requires background information on a variety of interlinked topics — to the point that a two-part article was necessary.

In part one, we will define the relationship between crypto and “aggregation theory,” a topic that was originally introduced by Stratechery in the mid 2010s to describe web2 business models pioneered by Airbnb, Netflix, and Uber. We will delve into the fundamentals of aggregation theory and demonstrate its relevance to the crypto space, diving into how the theory needs to be modified to reflect the nuances of crypto, which leads us to define the crypto aggregation theory.

In part two, we will shift our focus to the burgeoning “bridge” industry, scrutinizing it through the lens of the now defined connection between crypto and aggregation theory. We aim to provide a deeper perspective of how we believe bridge aggregators can harness flywheels of network effects to drive their success and secure a competitive edge in the rapidly evolving blockchain landscape.

Let’s dive in!

Web2 Aggregation

Pre-Internet Era

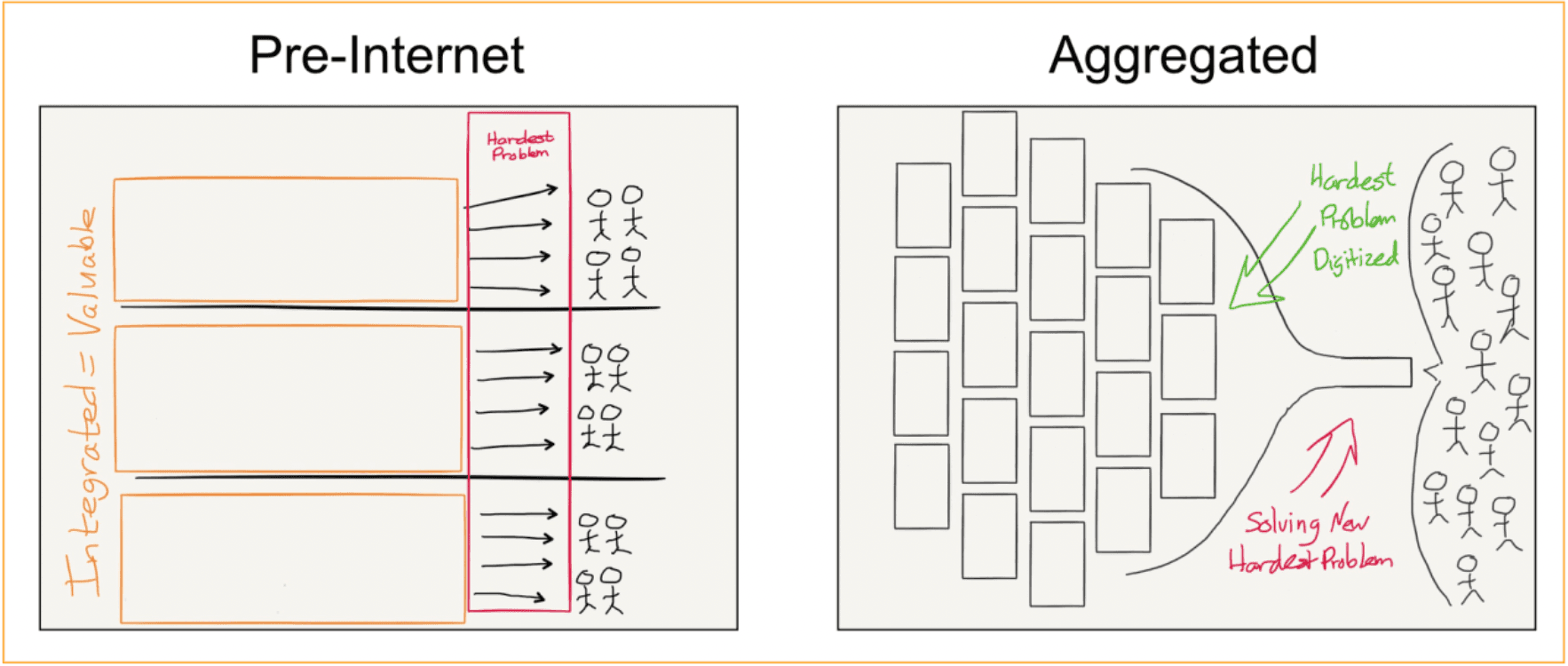

In the pre-internet era, retailers had restricted reach and obtaining information was challenging for consumers. Distribution was localized (which limited the number of users a company could serve) and suppliers were unorganized (leading to high transaction costs for users).

The hotel industry and its lack of efficiency is a good example of a pre-internet era business model.

Case Study: Traditional Hotel Industry

In the pre-internet era, the supply side of the accommodation market largely consisted of unorganized, expensive hotels. For travelers, finding accommodations was often difficult and unpredictable. They had to rely on travel agencies, brochures, or recommendations from friends to identify suitable lodging options. In other words, there was a limited variety of options available to travelers in terms of accommodation types, prices, and locations.This uncertainty led to issues such as:

1) limited availability of rooms during peak seasons

2) lack of transparency in pricing and quality of accommodations

3) limited choices for travelers with specific needs or preferences

Additionally, travelers often had to physically visit or call hotels to make reservations, which added inconvenience on top of inconvenience.

In the pre-internet era, hotel chains built monopolies in local zones by controlling the distribution of services. Hotels were the primary option for travelers seeking accommodations, as only a few well-established chains dominated the market. Travelers in need had limited access to information about lodging options in new areas. As a result, they frequently resorted to existing well-established hotel chains with established distribution channels and brand recognition.

Furthermore, hotel chains dominated the accommodations industry by integrating backward through partnerships with information providers. (An example of backwards integration would be hotels partnering with travel agencies, which helped them gain control over its supply chain and secure a significant share of bookings before a customer’s trip even began.)

However, the rise of the internet and the emergence of new business models would dramatically change this landscape. One key framework that helps us understand this transformation is Ben Thompson’s Aggregation Theory, which sheds light on how the internet has disrupted traditional industries (like hotels) and enabled the success of aggregators like Airbnb, Netflix, and Uber.

Disruption of the Internet

Markets change over time thanks (predominantly) to technology, with the last twenty years in economic trends being primarily influenced by the internet.

The 2000s and 2010s emphasized technology’s hold on the economy. The internet drastically changed consumer trends and market leaders in a short period of time via the advent of instant communication, borderless connectivity, and mobile-device usage — a trio of characteristics that, when combined, laid the foundation for the domination of “aggregators.”

The most famous and successful internet tech companies (Amazon, Uber, Netflix, Airbnb) in the world are, in reality, aggregators. These companies transformed industries through digital convenience and when you look at these projects from the lens of Ben Thompson’s aggregation theory, it makes perfect sense why.

According to aggregation theory, “the value chain for any given consumer market is divided into three parts: suppliers, distributors, and consumers/users.” Aggregators streamline consumer markets into a single funnel — in other words, aggregators combine suppliers, distributors, and consumers/users into a single application.

With the advent of the internet and birth of aggregation, the dynamics of consumer markets transformed. Distribution became free because information was easily accessible over the internet in just a few clicks. Furthermore, transaction costs dropped to zero as transactions were digitized. As a result, the competitive advantage that pre-internet companies gained by integrating with suppliers was effectively neutralized. In totality, the internet era found itself dominated by companies that provided a better user experience by simplifying how to best use available information.

Let’s take a look at how one popular aggregator was able to disrupt the hotel industry that we outlined above.

Case Study: Airbnb Disrupts Traditional Hotel Industry

Let’s go back to the hotel industry for a second. Before Airbnb, on the supply side, smaller property owners and operators faced significant barriers to entry because hotel chains had extensive marketing and distribution network effects established in the physical world. Consequently, many potential accommodation providers, such as individuals with spare rooms or vacation homes, could not effectively participate in the market.

As an internet-based platform, Airbnb revolutionized the accommodation industry by addressing supply and demand challenges. Airbnb expanded the supply of accommodations available by connecting travelers directly with property owners, thereby allowing diverse and affordable home-style lodging options to come into the market. Additionally, the platform made it easy for consumers to search for accommodations based on personal preference, budget, and location.

Airbnb organized the supply side, i.e., property owners, by providing a user-friendly platform to list spaces and reach a global audience. This allowed individuals with spare rooms, apartments, or homes to participate in the market without extensive marketing or distribution channels. The increased supply of accommodation options, reduced transaction costs and created new opportunities for individuals and small businesses to generate income.

On the demand side, travelers suddenly had more options for travel bookings. In addition to hotel rooms, they could now book a home-style accommodation in any location from the convenience of their computer/phone with the assurance of the host’s reputation.

After Airbnb organized the supply side, travelers had options to choose from in terms of the type of accommodation they want — third party managed hotel rooms OR self managed, home-style Airbnbs.

Airbnb leveraged the power of the internet to create a more efficient and flexible market. It empowered travelers and property owners by removing barriers and inefficiencies reminiscent of the pre-internet era — leading to a more diverse and competitive marketplace. As a result, it went on to dominate its niche as an aggregator and continues to do so.

On Aggregators in Web2

Aggregators blossomed across a variety of industries in the 2000s and 2010s. Searching for information? Google. Buying goods online? Amazon. Watching a TV show? Netflix. Booking a cab? Uber. Streaming music? Spotify. Ordering food? Zomato/Deliveroo/Uber Eats.

All platforms mentioned above are aggregators and successfully managed to bring order within the chaos of their industry niches. According to Thompson’s aggregation theory, each of these companies can be defined as platforms with the following characteristics:

direct relationship with users (there is an app for that) — Aggregators interact directly with their users, meaning they can control the user experience and collect valuable user data to further enhance and personalize their services (and perhaps even sell the data as part of their business model).

zero marginal costs for serving users (internet makes providing a service to users cheap) — For an aggregator, the costs associated with serving marginal customers , aka new users who join the platform, as it continues to grow are negligible or virtually nonexistent because the nature of the service offering:

— digital: can be replicated infinitely at virtually no cost

— delivered via the internet: zero distribution costs, and

— done via automated systems: transaction costs don’t increase linearly with the increasing number of users.

demand-driven multi-sided networks with decreasing acquisition costs (more adoption leads to more adoption) — Aggregators create a network effect where their platforms become more valuable as more users and suppliers join. They initially attract users by offering better discovery and curation of digital goods. As the user base grows, suppliers are drawn to the platform, which in turn attracts even more users. This cycle continues, and the cost of acquiring new customers decreases over time, leading to a winner-take-all market dynamic that benefits the aggregator.

The characteristics of aggregators make sense in Web2. By leveraging the internet to reduce distribution expenses, these platforms have succeeded in consolidating diverse service providers within a specific market onto a single platform for users.

Aggregators in crypto exhibit similar characteristics to aggregators in Web2 at the platform level. However what it takes for them to create similar network effects is significantly different since the foundational tenets of crypto are different than those of web2. Let’s look at aggregation and aggregators in crypto and understand how things are different.

Crypto Aggregation Theory

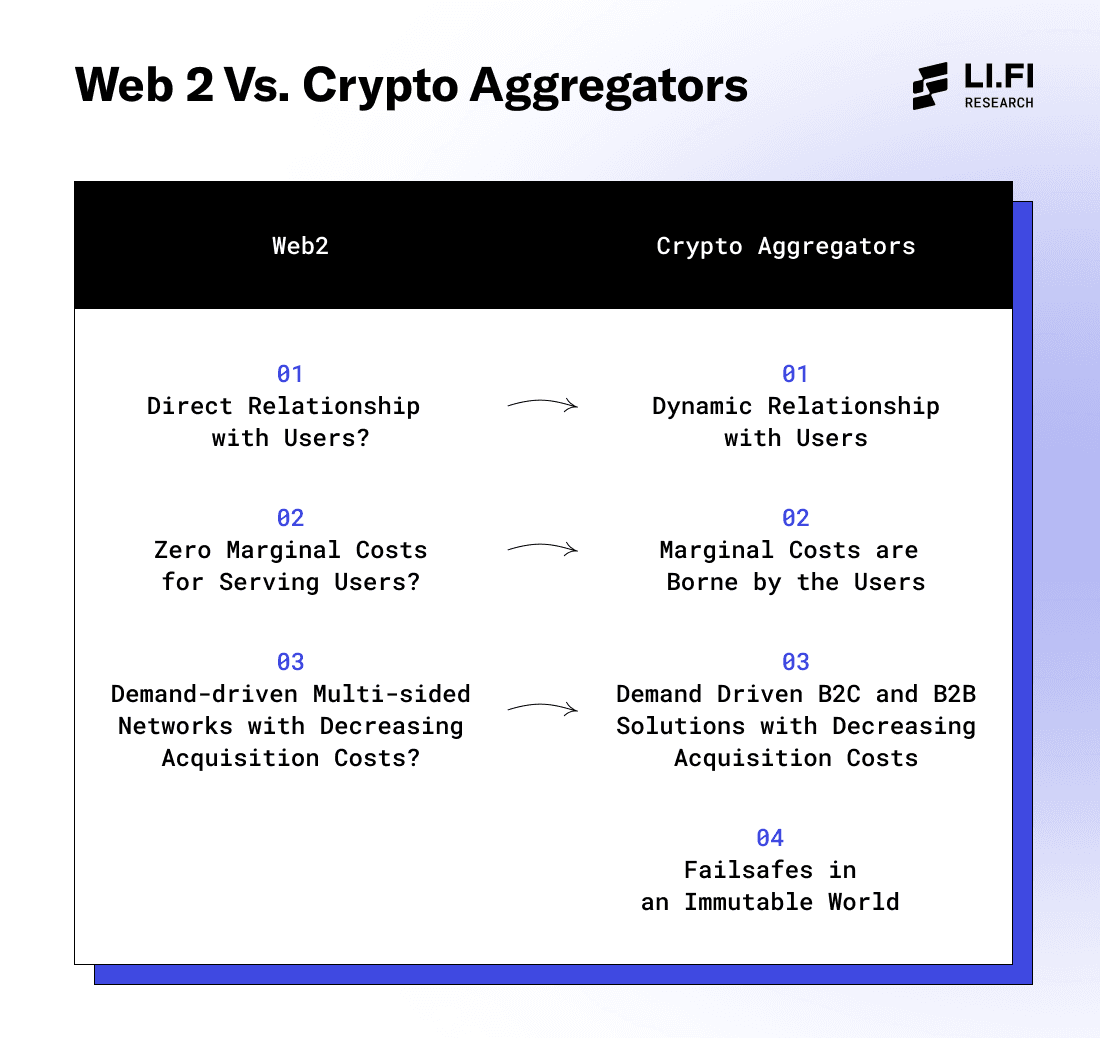

Aggregation in crypto, specifically in the context of decentralized finance (DeFi), differs from aggregation in Web2 in several critical aspects since the foundational characteristics of crypto are different from those of the internet. Let’s take a look at the three characteristics of aggregators laid out by Ben Thompson and fine-tune them for crypto. Additionally, we would like to add an extra characteristic to the aggregation definition for crypto.

1. Direct Relationship with Users? → Dynamic Relationship with Users

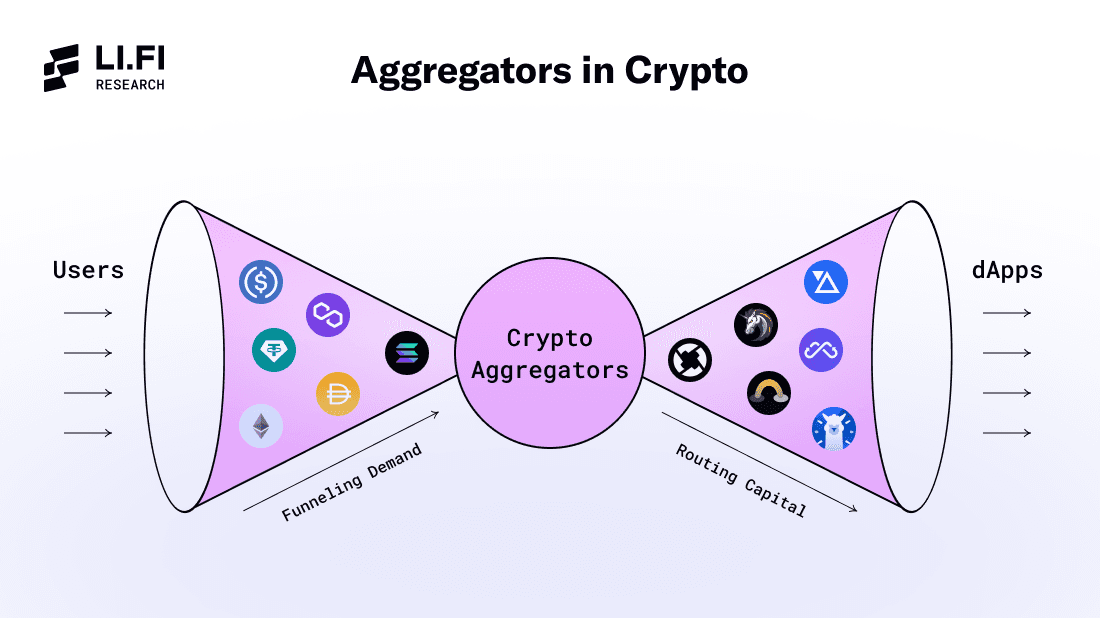

Crypto aggregators collect user attention and funnel it into DeFi protocols — they co-ordinate the exchange between supply-side (protocols) and the consumers (users) of the service.

In this way, crypto aggregators are quite similar to web2 aggregators. They remove the complexity and streamline the user experience for end-users by offering a comprehensive view of available options and optimizing the decision-making process and execution of transactions. In other words, aggregators direct end-users to the right service provider based on personal requirements and capture value through the convenience and efficiency offered.

Because of their position in the middle of the supply (protocols) and demand (users) dynamic in crypto, aggregators play a critical role in determining how capital flows across the DeFi ecosystem — they are routers and/or allocators of capital in crypto. For instance, DEX aggregators determine which DEX gets volumes for swaps, yield aggregators determine where the users’ capital will be allocated, bridge aggregators determine which bridge provides the most efficient route for a cross-chain transaction, etc.

So, yes, users can directly interact with crypto aggregators on their B2C-focused interfaces. Example: Matcha.

But, there’s a big caveat here and that’s what makes this relationship dynamic. In crypto, users are not loyal to any platform and thus it’s much more difficult for crypto aggregators to scale user relationships and build moats because of tokens.

Why crypto aggregators find it difficult to scale user relationships like Web2

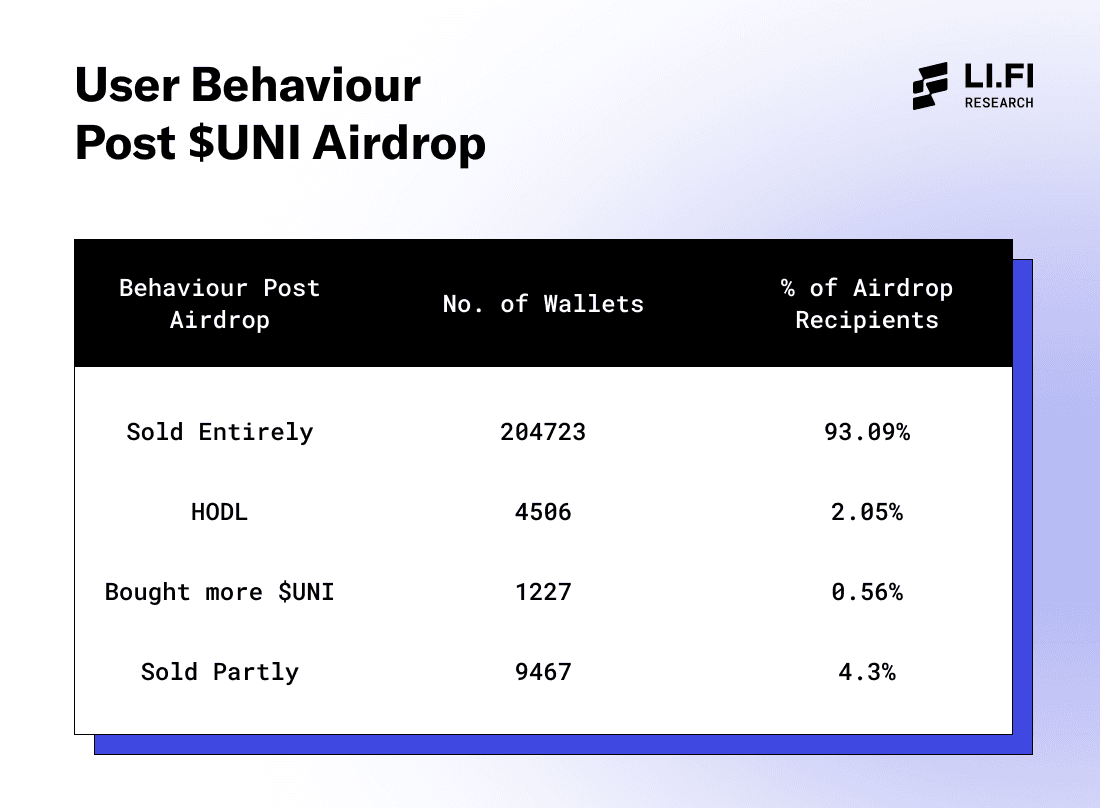

In crypto, it appears users prioritize returns over loyalty to specific aggregators. Capital flows to wherever it can make the most money, and because switching costs are almost nonexistent, users can easily move to another aggregator offering better services, returns, or token incentives. Here’s some data that shows users in crypto are not loyal to any platform:

Only ~6.91% of wallets that received the Uniswap airdrop in 2020 are still holding $UNI (~93.09% sold their $UNI airdrop within a year).

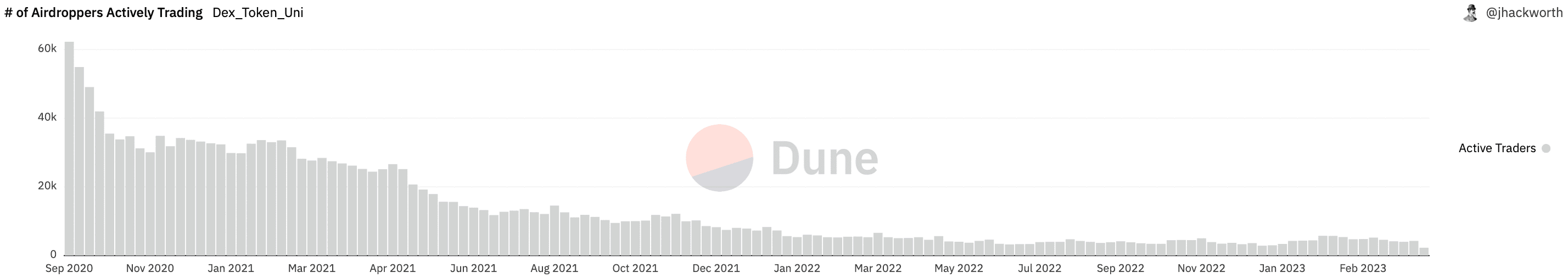

$UNI airdrop recipients actively trading on the platform reduced significantly after the airdrop. In mid-September 2020, there were over 62k weekly traders, which dropped to around 10k a year later and by September 2022, the number had further reduced to a mere 4k (Note: most of these wallets are now inactive on Ethereum, with only ~2.3k active this week).

Out of approximately 1.4 million ParaSwap users only 20,000 ‘active user’ wallets were eligible for the $PSP airdrop. As a result, many ‘users’ abandoned ParaSwap (ParaSwap blacklisted sybil attackers from the list of eligible wallets for the $PSP airdrop).

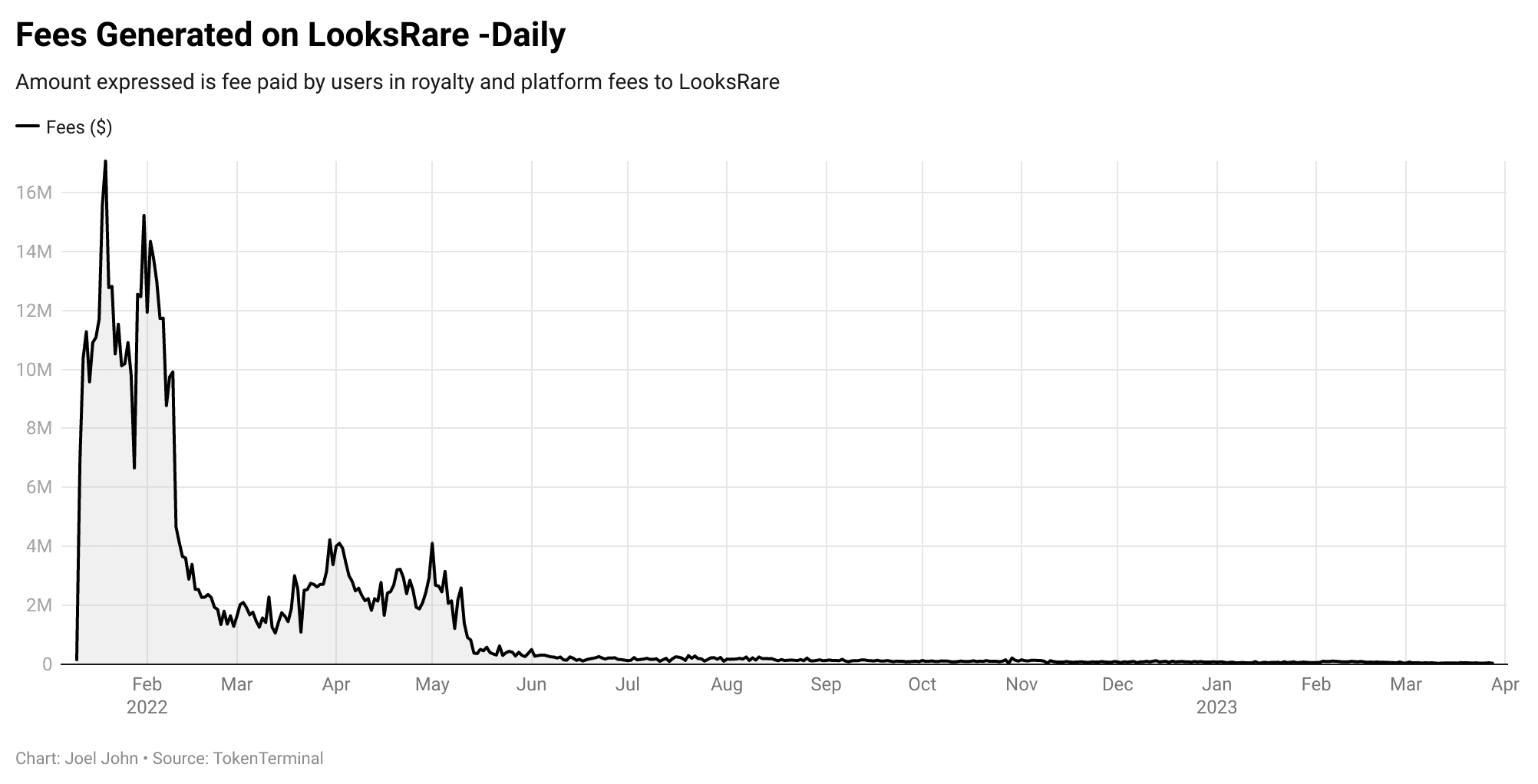

In January 2022, LooksRare orchestrated an airdrop of $LOOKS tokens with the aim of enticing high-volume users away from OpenSea (LooksRare platform fees are designed to be distributed among $LOOKS token holders). The token incentives only had temporary user retention powers, as can be seen from the chart below.

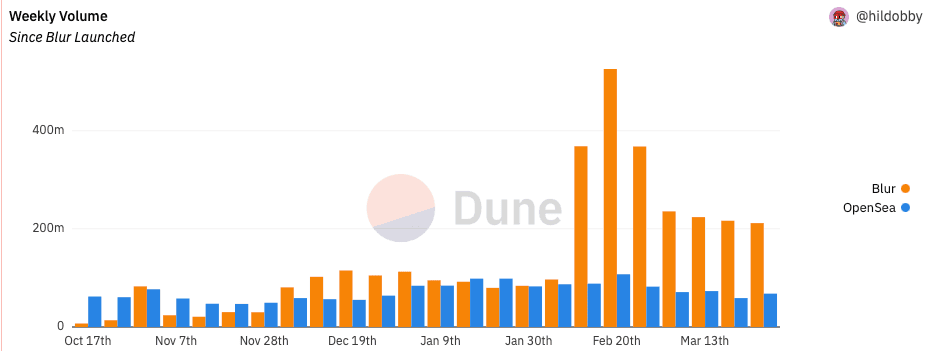

Blur’s token incentives overthrew OpenSea from its throne — While Blur had been dominating OpenSea in terms of trading volumes over the past 6 months, the volume on the marketplace blew up post the airdrop on 15 February this year. This forced OpenSea to make significant changes to its operations for the first time in years.

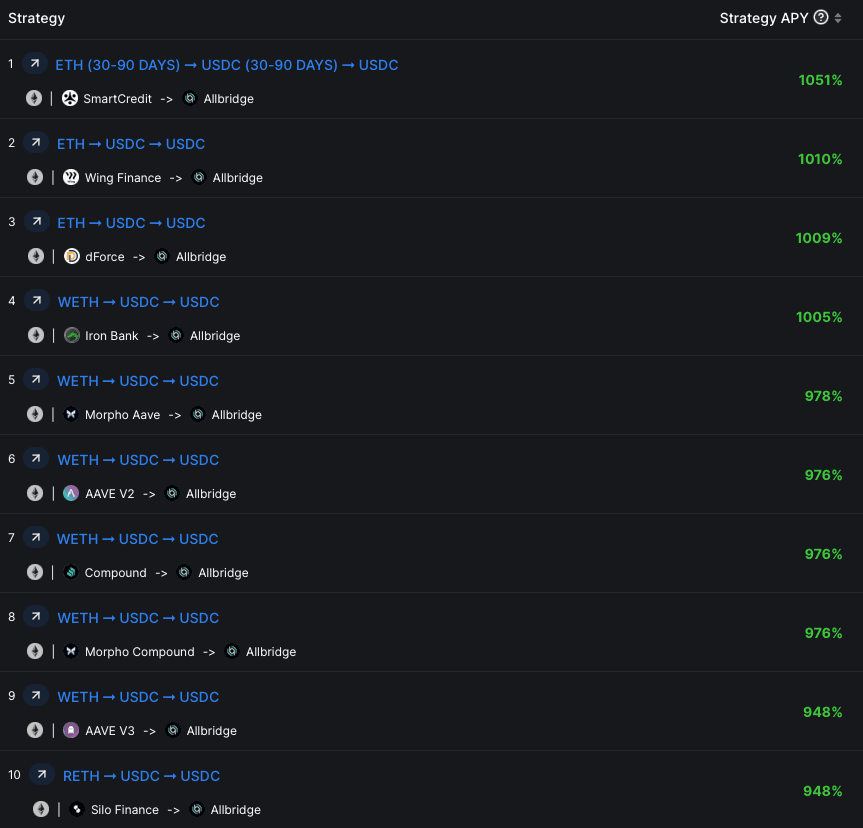

Capital in crypto flows wherever there’s an opportunity to make the most returns and this can be seen by the multitude of yield optimization platforms (>90 listed on DeFiLlama) such as: Yearn Finance (TVL > $400M), Beefy Finance (TVL > $350M), among others. Moreover, there exist several tools that help users find the best way to use their funds — such as DeFiLlama’s Delta Neutral (“lend-borrow-farm” strategies across all DeFiLlama tracked pools) and Long-Short Strats (delta neutral “long-short” strategies across all DeFiLlama tracked pools and CEX perpetual swap markets).

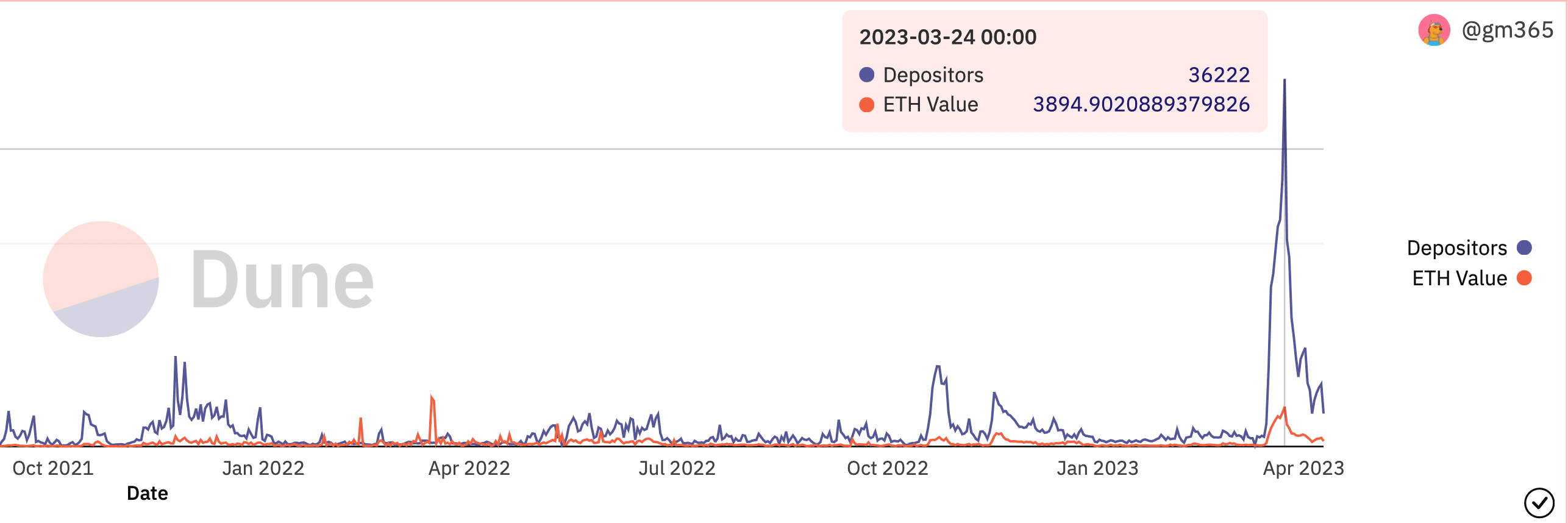

After Arbitrum’s airdrop of its native token $ARB was confirmed on March 16, users bridged millions to zkSync and Starknet in the hopes of farming a potential airdrop in the future.

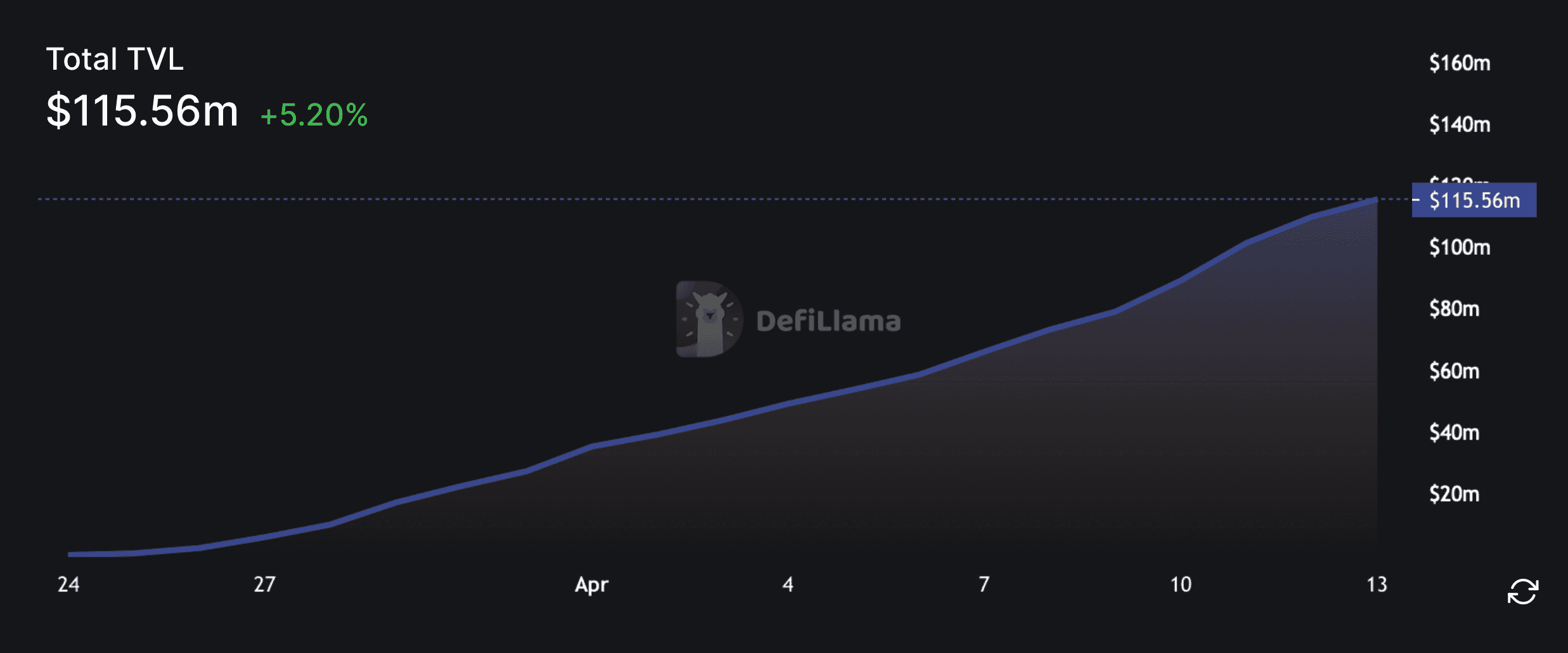

Similarly, zkSync’s newly launched Era’s TVL skyrocketed to over $115M in approximately two weeks. (In the same time, Polygon zkEVM’s TVL remains relatively low at ~$12M since there’s no possibility of a potential airdrop of a native token for the chain).

to wherever there’s an opportunity to make the most return.

The same applies to aggregators in crypto, and as a result, there always needs to be some incentive or reason for them to stick to one aggregator. Consequently, crypto aggregators have to bear additional ongoing costs of user acquisition and platform development to retain users and remain competitive. Such costs include:

Token incentives — The cost of allocating tokens for rewards or liquidity mining programs can be considered a form of user acquisition or retention cost.

Integration costs — Crypto aggregators must integrate multiple protocols and blockchains to offer a seamless experience to their users. This integration process requires ongoing development and maintenance overhead, which incurs costs.

Examples:

For bridge aggregators, it’s imperative to constantly add support for new blockchain ecosystems to attract new users.

For NFT marketplaces like Blur, it’s imperative to continue offering token incentives to users to compete with other projects in the niche that offer similar incentives.

Moreover, a major distinction between Web2 and crypto aggregators is that crypto aggregators allow direct ownership of a solution via token governance, which allows users control further permutations of the aggregator. As a result, users switch to different platforms because they can have direct ownership (an example specific to the crypto industry) — users are more inclined to support and use platforms that offer them token rewards.

Another distinction between web2 and crypto aggregators is the extensibility of the term “end-user.” In the web2 world, an end-user is often an individual or customer. However, in the crypto world, many aggregators are being used as part of wider B2B offerings, meaning an “end-user” in crypto might be a different protocol. (more on this in #3)

2. Zero Marginal Costs for Serving Users? → Marginal Costs are Borne by Users

A fundamental difference between crypto and traditional aggregators is that the burden of marginal costs shifts away from platform to individual.

Since crypto aggregation is provided by leveraging blockchain technology and smart contracts, crypto aggregators do not incur any additional costs to serve a new user. Instead, it’s the users who bear the marginal costs in the form of gas fees for executing various transactions and interactions with smart contracts that are bundled together via an aggregator. This differs from traditional aggregators, where the platform often incurs marginal costs related to serving additional users.

Thus, crypto aggregators incur none of these costs:

Cost of goods sold — facilitated via blockchain technology and smart contracts (though there are several fixed and ongoing costs as discussed in #1)

Distribution costs — similar to traditional aggregators, crypto services are distributed via the internet.

Transaction costs — gas costs for executing transactions at the smart contract level and settling them on the blockchain are borne by the user.

3. Demand-driven Multi-sided Networks with Decreasing Acquisition Costs? → Demand Driven B2C and B2B Solutions with Decreasing Acquisition Costs

The last characteristic says that when aggregators attract users to the platform by offering superior discovery (i.e., organizing the chaos on the supply side and enabling users to find the best solution based on their needs through discovery and curation), they become more attractive for a new supplier to join. This should create a virtuous cycle wherein the more suppliers on the platform an aggregator supports, the more attractive the aggregator is to the users, thus decreasing the cost of acquiring customers for the aggregator. Eventually, this leads to one aggregator platform successfully cracking the flywheel of network effects to emerge as the ‘winner takes all’ protocol.

This is partly true for crypto, though a bit more difficult to pull off in comparison to Web2.

Crypto aggregators build network effects by retaining users on the front-end level and gaining adoption on the protocol-level through B2B integrations — like Joel John said, “a firm can simultaneously be a tool of novelty and convenience if it sells to power users” — meaning aggregators can build network effect flywheels by serving powers users (aka degens) on the B2C side by offering novelty in a complex product niche and protocols on the B2B side by becoming a tool of convenience.

In other words, crypto aggregators build user retention moats by owning distribution in a niche on the front-end level (i.e., become the hub for all things related to a niche) while also focusing on increasing the adoption of their tech through B2B integrations that allows them to drive users through the efforts of other protocols. Achieving adoption at scale is critical for the success of a crypto aggregator because they are minimally extractive by design and often either don’t charge anything or take a small fee for their services.

To this end, we believe that aggregators are well positioned to become the middleware layer between blockchains (L1, L2s) and consumer facing dApps (Uniswap, Opensea) that can unlock crypto’s potential to onboard the next billion users.

However, we recognize that the above virtuous cycle is difficult to create in crypto due to the open source nature of the space. Since all dApps on the supply side can be easily integrated by any aggregator (because most dApps are open-sourced in crypto), all aggregators can potentially offer the same value to users (at least in terms of options offered). For instance, 1inch and Matcha (competing DEX aggregators) can have all the same DEXs in their stack at a given time.

Thus, it appears the multi-sided network effects fail to take off in crypto because the suppliers (protocols) are open source and universally accessible whereas on the demand side, users in crypto are not loyal which makes it difficult for aggregators to scale user relationships and build moats. This unique environment prevents a “winner-takes-all” scenario from emerging among crypto aggregators, as competitors can easily fork, execute vampire attacks, or reduce fees to remain competitive. So, instead of demand driven multi-network effects, we believe that B2C and B2B adoption of a crypto aggregator will be what generates a flywheel effect, rather than the flywheel being pushed by suppliers joining an aggregator, as it is in web2.

4. Failsafes in an Immutable World

Crypto networks like Ethereum and dApps like Uniswap are innately open-source, permissionless, and thus transparent and auditable. Additionally, crypto applications, protocols, and other tools are immutable — meaning that once a transaction occurs, it cannot be changed.

This combination of open-source technology and immutability is powerful and has led to the creation of advanced financial tools that are available to essentially anyone with an internet connection. However, a drawback of open-sourced, immutable finance is that a single point of failure, be it smart contract, bad UX, or a network attack, can lead to irreversible losses for individuals and businesses interacting with crypto primitives. This is obviously different to the web2 world, where financial institutions and internet based companies are not constrained by blockchains.

Crypto aggregators offer an extra layer of protection against losses, as each interaction with an aggregator sources options from multiple venues, thereby minimizing the spread that a single compromise may have on the crypto ecosystem at large.

Crypto Aggregation Reality (Aggregators in Real Life)

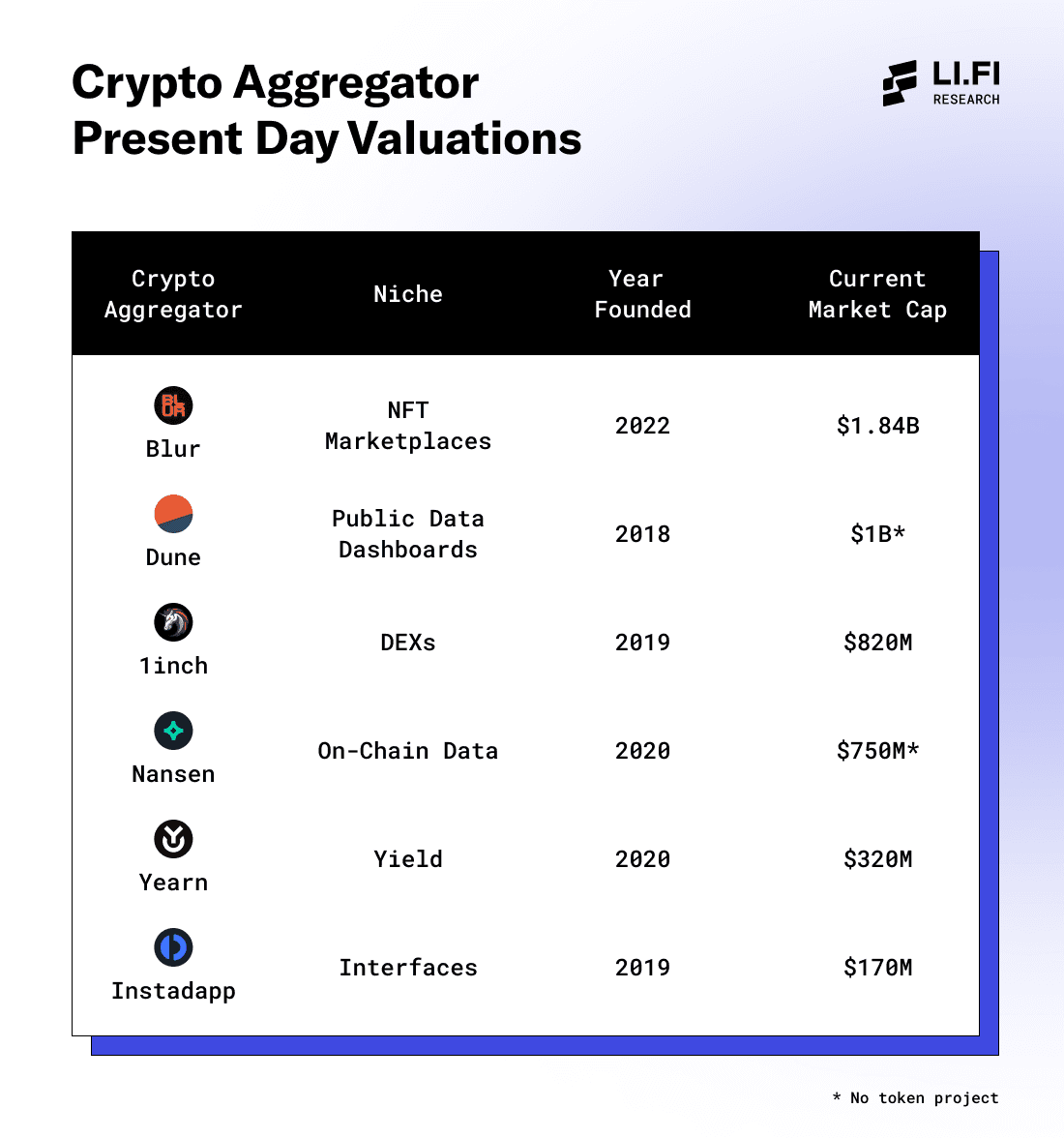

Currently, the landscape of aggregators in crypto looks something like this:

The reality of crypto aggregators is that aggregators do not dominate the crypto space as their web2 counterparties dominate web2. In fact, an aggregator has yet to overtake a niche in crypto despite being able to offer more options to users and a seamless user experience — though we believe this will change over time. Here is a list of aggregators (italics) and the non-aggregator industry incumbent that ranks first in historical volume, clicks, TVL, etc (bold).

NFT marketplaces — Blur and Gem, OpenSea

Bridge aggregators — LI.FI (Jumper) and Socket (Bungee), Multichain

DEX aggregators — Matcha, 1inch and Llama Swap,Uniswap

Yield aggregators — Morpho and Yearn, Aave

Perp aggregators — MUX Protocol and UniDex Exchange, GMX

Interface aggregators — Zapper and Zerion, MetaMask

We believe this is due to the crypto industry’s nascent age. The crypto industry is still in its infancy and it seems users and developers prefer to stick to dApps they know how to use and trust — as the industry matures and aggregators become more complete in their service offering, aggregators will gain more dominance in their niches against individual service providers (Example: Matcha vs Uniswap). Just like early internet sites might have seemed dominant forever, aggregation ultimately won out, and we think it will be similar in crypto.

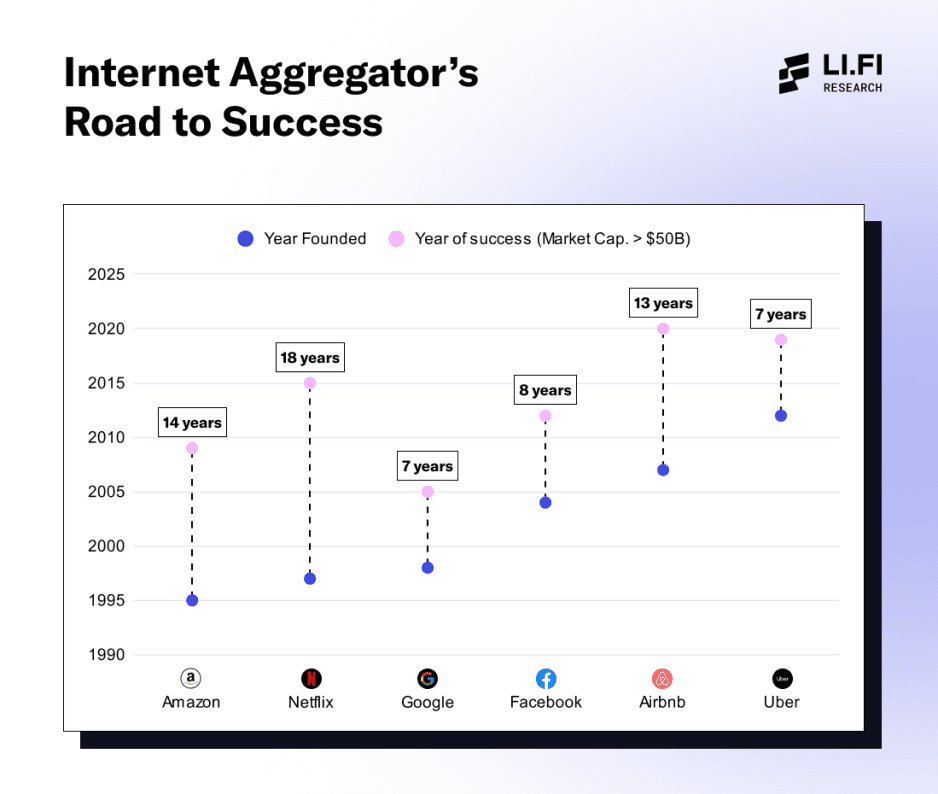

The current state of crypto aggregators is reminiscent of the early days of internet aggregators, standing on the precipice of potential growth and dominance as the industry matures. Like their web2 counterparts in the nascent stages, crypto aggregators have yet to overtake their respective niches. Still, the possibility of achieving a similar scale, if not surpassing it, looms on the horizon.

It’s worth noting that the pace of technological advancement is far more rapid today than it was during the early days of the internet; this accelerated growth could propel crypto aggregators to reach prominence and influence in even less time than it took their web2 predecessors. By drawing parallels with the rise of internet aggregators, we can envision a future where crypto aggregators ultimately gain dominance in their niches, driving innovation and transforming the blockchain landscape.

An important note to back up our enthusiasm for aggregators here is that dApps in crypto have still created tremendous network effects despite the challenges of open-source technologies and lack of aggregator dominance. We’ve seen time and again that DeFi is a game of monopolies and ‘winner take all’ scenarios seem to exist. As mentioned above, projects like Uniswap (among DEXs) and Aave (among Lending protocols) are leading their respective markets since they’ve successfully created a flywheel of network effects largely through:

1) first mover advantage

2) superior user experience

3) robustness and reliability in tech

4) partnerships and integrations

5) brand recognition, among other reasons.

We believe that as the industry matures, some of these blue chips like Uniswap and Aave will either 1) become aggregators themselves (Uniswap and Opensea have already made steps to do so) or 2) be challenged by an aggregator. Indeed, aggregators are seeing the success of aggregators in non-DeFi primitive areas:

On-chain data platforms — Nansen and Arkham Intelligence

Public data dashboards — Dune and DeFi Llama

Centralized exchanges — Coinbase and Binance (s/o FTX)

Crypto market data platforms — CoinGecko and CoinMarketCap

Interfaces — Zapper, Zerion, Instadapp

We believe aggregation will win in crypto, just as it did in web2. Aggregatorsare poised to dominate the space as they construct robust user retention moats by commanding distribution within a niche on the consumer-facing side and solidifying their role as a vital middleware layer in DeFi. Although initiating such a flywheel of network effects presents its challenges, it is by no means insurmountable for aggregators.

To further our thesis on why we believe aggregation is the future of crypto, we will narrow down the scope to bridge aggregation.

[We will explore how bridge aggregators can create similar network effects and emerge as winners in the bridge wars in the section: bull case for bridge aggregators]

Don’t miss Pt. 2 of our series, “Bridge Aggregation in a Multi-Chain World,” which will provide a detailed analysis of the factors that will determine the success of bridge aggregators. We’ll examine the need for bridge aggregators, how they work, their role in the multi-chain ecosystem, and the potential pitfalls they may face in their quest for dominance.

See you soon, with some words on bridge aggregation :)

Huge thanks to Mark Murdock for brainstorming the crypto aggregation theory and co-writing this research article. 😄

FAQ: Crypto Aggregation Theory (ft. Bridges)

Get Started With LI.FI Today

Enjoyed reading our research? To learn more about us:

- Head to our link portal at link3.to

- Read our SDK ‘quick start’ at docs.li.fi

- Subscribe to our newsletter on Substack

- Follow our Telegram Newsletter

- Follow us on X & LinkedIn

Disclaimer: This article is only meant for informational purposes. The projects mentioned in the article are our partners, but we encourage you to do your due diligence before using or buying tokens of any protocol mentioned. This is not financial advice.